The story of Harry McNeish

THE KNIGHT, THE CARPENTER AND THE CAT

This account is a shortened version of John Thomson's talk given to the Karori Historical Society in September 2005. Tales from the Antarctic Pasta, a typographical error in a programme John was presenting on board a tourist ship. John is also author of two books Shackleton's Captain and Elephant Island and Beyond, The life of Thomas Orde Lees.

|

The plethora of books, films, documentaries and newspaper articles about Sir Ernest Shackleton, particularly in the past decade, has ensured that the great explorer/adventurer will be remembered for at least the next century. And in that time more can be anticipated. His descendents and the international James Caird Society will be sure to keep his two notable achievements -- the 1909 attempt to reach the South Pole and the failed 1914-16 expedition aimed at crossing the continent via the South Pole -- alive. Opinions about Shackleton vary, and some people would describe him as adventurer/survivor rather than explorer/adventurer. Either way, he was an exceptional man whose friends generally remained faithful, and whose critics are generally written off as mean-minded and petty. Here safe and snug in Karori Cemetery, where he has resided for 75 years, is a man who had more reason than most to curse Ernest Shackleton as being possessed of both the negative qualities usually reserved for those who choose to see the great man in a different light. His headstone gives the name Harry McNeish, but that could have been McNish: it depends on which part of the Scottish family from whence he came you are talking to. But for official purposes, Harry must have declared he was a 'McNeish', for that is how he was described in papers for the ship Endurance when he was hired as carpenter for a journey of exploration in 1914 that became a wonderful story of survival more than two years later. And his part in that adventure is penned home to 'McNeish' in the official records and the definitive book on the expedition. |

Why would Harry McNeish have had hard feelings about the nation's hero, Shackleton, knighted by his king for bringing glory to his country for the 1909 drive for the South Pole that ended barely 100 miles short of the target?

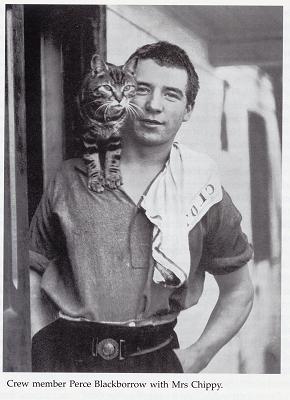

For a start, Shackleton ordered the destruction of McNeish's pet cat, the much-loved Mrs Chippy, when all hands had to abandon the Endurance and live on the sea ice of Weddell Sea along with the sledge dogs who had been tormented at sea by the cat, and who would have torn Mrs Chippy to pieces in minutes off the ship.

That action, in McNeish's eyes, was the ultimate insult: Totally unforgivable.

Shackleton, who had now failed twice to make the Pole, the first with Scott during the National Antarctic Expedition of 1900- 1904, and again with his own expedition in 1909, subsequently planned the crossing of the Antarctic via the South Pole, the second phase of which was to be supported by the Weddell Sea Party. For this he needed a lot of money. He bought a near new ship, renamed her Endurance, established a London office to equip her with the manpower and stores for a year-long expedition. He selected Harry McNeish as ship's carpenter, a sufficiently important role in the days of wooden ships, to rate, a somewhat lowly place, on the wardroom staff. Orders for the expedition came from Shackleton "The Boss" or Frank Worsley, the ship's captain; those in the wardroom were responsible for carrying them out. Once discussed and delivered they were to be obeyed without question.

McNeish, born in Glasgow in 1874, was a man of strong ideas, crafted in the cradle of a shipwright, but skilled in work with iron and wood. By birth, nature and upbringing he was more at home with the crew.

When the Endurance sank, the 28 so-very-disparate men were ordered to manhaul three lifeboats over rugged ice vaguely in the direction of the ice-free ocean to which they would ultimately have drifted. McNeish, whose view was tacitly shared by Worsley, felt the labour lacked good purpose and would damage the boats on which their lives depended.

Exasperated, one morning he refused to push or pull the little boats over any more rough ice and challenged Worsley and the order of Shackleton. Because there was no ship they were not subject to its Articles, a code by which the crew was bound to the vessel through the captain. Out of the sea ice the crew stood back and awaited developments.

Shackleton arrived, heard the complaint and in a moment of sheer genius turned the whole situation to his advantage with a virtual lie that the crew were on full pay, which they had expected to have ceased when the Endurance sank. He emphasized that he, not Worsely, was the man to be obeyed. Though McNeish was technically correct, the crew eagerly accepted Shackleton's idea and the stand was undermined. In the privacy of his tent McNeish was logged for his refusal to obey the lawful command of Worsley (not, it should be noted, Shackleton) the leader whose order it really was). Shackleton threatened to shoot him in the event of any further infraction.

From then on McNeish's actions were nothing short of excellent and his work on the lifeboat James Caird greatly enhanced the success of the 16-day journey from Elephant Island to South Georgia that was vital to the rescue of the 22 men left on the island.

Shackleton, however, had been greatly shaken by the experience. The mutiny, led by McNeish, had gone close to taking the tattered expedition deeper into disaster. He never forgave him, and although admitting McNeish was a very good workman and shipwright he recorded that "I shall never forget him in this time of strain and stress".

And he did not. McNeish was one of four members of the expedition denied the Polar Medal. He seemed to put little importance on the medal; he was struck more powerfully by the fact that Shackleton "shot my cat."

After the rescue members of the party went their various ways, many of them straight into the Great War. McNeish went back to sea and in 1925 he migrated to New Zealand and worked on the Wellington wharves for the New Zealand Shipping Co. The rigours of the Antarctic adventure, and in particular the draining ordeal of the James Caird voyage, had left the carpenter somewhat crippled in his bones: he complained of perpetual aches, and at some stage he had an accident at work and lost his job.

The Great Depression was approaching and times were hard for ageing men without the capacity to work, and McNeish was greatly assisted by the brotherhood of the waterfront in finding an occasional warm corner for a good sleep, and a weekly pittance for some of life's little comforts. Finally he found a permanent bunk at the Ohiro Home for Men, where he died in September, 1930.

And then another side to Harry McNeish was revealed. Based on accounts of his adventurous life no doubt passed to workmates in wharf gossip, it was widely believed that he had had more than one Antarctic adventure: his obituary stated that he had been on Scott's 1901 expedition, had helped build Scott's vessel, the Discovery, sailed on her as carpenter and spent two years at Hut Point on Ross Island. He had also declared 23 years' service in the Royal Navy.

Even members of his family today agree none of this was true, except perhaps for some years in the Royal Navy, but in 1930 McNeish's account was accepted and friends decided that such a man deserved a serviceman's funeral, even one destined for a pauper's plot at Karori.

With the help of a friendly Member of Parliament, the Government assisted with arrangements and provided the plot. The NZ Army provided a gun-carriage and the crew of a visiting Royal Navy ship, HMS Dunedin, provided pall-bearers and a firing party for their departed comrade. So Harry McNeish, a deserving man in so many ways, got something he didn't really deserve, something that none of his mates on Shackleton's daring expedition aspired to: a fleeting moment of national recognition in an adopted country that was then spoiled by the failure to mark his grave appropriately.

McNeish became a forgotten man until the New Zealand Antarctic Society, through local member the late Arthur Helm, started to ask questions, the plot was traced and in 1957 the present headstone was erected. As we know, it has been enhanced most thoughtfully by a beautiful sculpture of his loved cat Mrs Chippy (in fact a male cat, but then McNeish as carpenter was already Mr Chippy) created in bronze by the Hawkes Bay artist, Chris Elliott.

From Stockade 39, 2006 Karori Historical Society